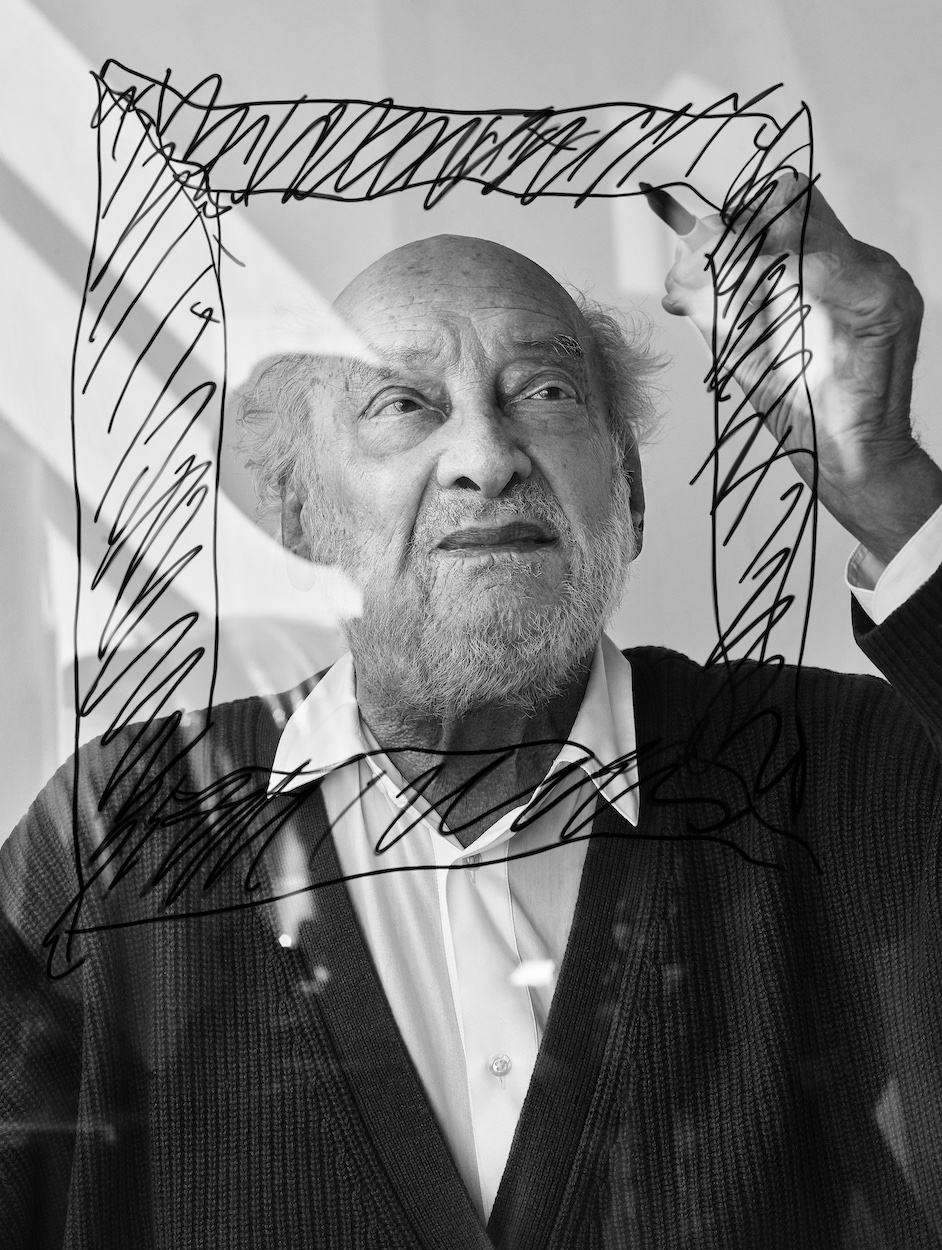

GAETANO PESCE BY ALBERT WATSON FOR Issue NO. 01

Credits

PHOTOGRAPHY Albert Watson

INTERVIEW Ruben Modigliani

“This occurred to me when looking at Michelangelo’s designs for fortresses, which convey the negativity of war. It was then that I realized that architecture does not always have to be a positive act of faith, it can also be a critique of a place, a regime, or a way of thinking.”

Gaetano Pesce: Are you related to the artist Modigliani? And where are you right now?

Ruben Modigliani: We are related, but I don’t know exactly to what degree. I’m in Milan right now, but I was born in Florence.

What should I call you – Maestro, Architect?

G.P: Just Gaetano.

R.M: How did your career in design start?

G.P: I was introduced to art by my mother, who taught me to play the piano, and about composers and how music represents its time. And when I finished school, she recommended that I study architecture. Then a fellow student and discussion partner helped me to see that the new expression of the moment was design. Even then, I already thought that an object should not be a mere commodity or an aesthetic or formal comfort. It had to be something more, to represent its time, and to tell stories beyond the merely practical. And architecture was part of this conversation because a building is an object on a large scale. International Style, with identical buildings the world over, made no sense to me. I thought—as I still do—that the diversity of different places should be expressed through architecture. The architect should not have just one language, but as many as there are places for his projects.

R.M: Your career has spanned fifty years of design history (or perhaps even more). What has changed and what has remained the same?

G.P: I am still convinced that the most important aspect of our craft is diversity. It is the premise of all my work, architecture as well as so-called design and so-called art.

R.M: Why do you speak of “so-called design” and “so-called art”?

G.P: Art is design, design is art. They are the same thing. Especially when design can express content more typical of art. It was a moment of great enlightenment when the world of culture recognized design. There are, of course, those who still believe design to be a second-rate creative expression. But they are all imbeciles.

R.M: If you had to summarize the meaning of your work in a few words, what would they be?

G.P: Curiosity. I don’t have a style – I am free of that. Recognition of the artist is no longer valid. Only cretins are coherent because they aren’t up to date. Diversity of language is extremely important. These are the ideas inspired in me by New York, the city where I live: not monolithic, but composed of minorities that coexist according to diverse values. It is a rich source of inspiration. From this perspective, I am sorry that Italy—which has formerly given the world such priceless values—has become a little sleepy and provincial. We have rulers who attend useless inaugurations instead of telling the country that it needs to wake up in order to develop local creativity that is deeply linked to our time.

R.M: In 2010, the Italian Cultural Institute of Los Angeles held an exhibition of your work entitled Pieces from a Larger Puzzle, which seems a particularly appropriate title. What image does the puzzle form?

G.P: My work is a puzzle that can never be completed. It is always in the making. I am 83 years old and everything is still working pretty well apart from my legs. Because I’m careful. I recently held a conference at Columbia University where the young students were enthusiastic to learn things they don’t hear at school. Schools should educate individuals with knowledge of today’s actual world, not of the past. It should also teach students to be optimistic, open and joyful, because life is an incredible gift.

R.M: If you weren’t an artist/designer, what would you have become in life?

G.P: A pianist.

R.M: Do you still play?

G.P: No, my hands aren’t flexible enough anymore. They haven’t been since about the age of 60 or 65. I used to turn the page for my mother when she was practicing.

R.M: Other than sustainability (environmental, social and human), where is design heading, in your opinion? And where should it be heading?

G.P: We are losing leadership in this sector in Italy because industries no longer understand how important innovation is. They are too preoccupied with making money, which is necessary but not the be-all and end-all. You have to think about tomorrow, too. Industry should be open to innovation. The Ministry of Culture should be pushing our industries further so we don’t lose ground.

R.M: Is there anything that you haven’t yet achieved but would like to?

G.P: The Pluralist Tower: a column of apartments, 40-50 floors tall, where every floor is designed by a different architect. A representation of democracy. The tower is designed to accommodate diverse lifestyles, cultures, and identities, and this plurality is clear from the outside. Unlike the skyscrapers we see around the world: authoritarian architecture, if not autocratic and dictatorial.

R.M: What brought you to New York? And what made you stay?

G.P: I left Italy at the age of 19: I went to London first, then Helsinki, and then Paris, so I was never too far from my mother. Then, when she died, I came to New York. It is a city of highly creative individuals. You can see the future just by observing how they talk, how they dress, how they judge, and how they invent things.

R.M: Assuming that attaching flags to design makes sense, what nationality do you consider yourself?

G.P: Totally Italian. The validity of the Renaissance lies in the fact that an artist cannot be tied to a single area: one day we are architects, the next we are sculptors or poets. It is a vision of the non-static nature of culture.

R.M: You have taught extensively. What are the connections between teaching and designing/creating?

G.P: Teaching is creating. And I have tried to teach as best as possible: I taught something new every time I entered a classroom. I never repeated myself. It was incredibly difficult, but it was also far more fulfilling. And that is what a student should be receiving. Not traditional teaching, where the professors teach the things they learned when they were young. These embody outdated values for obvious reasons. I have learned from my students very often.

R.M: Can you teach creativity? If so, how?

G.P: By provoking. At the architecture schools where I taught, both in NYC (Cooper Union) and Strasbourg (Institute for Architecture and Urban Planning), I asked students in their final year to design a “court of justice” for Moscow under Stalin’s rule. Or for Pinochet’s Chile. If they were against such totalitarian ideologies, they had to create a negative architecture to reflect this, which is unheard of. It was a way to help them understand that their works should reflect their way of thinking. This occurred to me when looking at Michelangelo’s designs for fortresses, which convey the negativity of war. It was then that I realized that architecture does not always have to be a positive act of faith, it can also be a critique of a place, a regime, or a way of thinking.

R.M: Many of the objects that you have created tie in to Zygmunt Baumann’s concept of ‘liquid modernity.’ Is there a link?

G.P: I don’t know this gentleman, but this moment is indeed liquid. That is why we must be free from ourselves, free from what was thought yesterday, and ready to understand the values of tomorrow. This instability is wonderful because it means every day is different. If we live our lives by simply repeating each day, we live for a single day. If every day is different, we live life to the fullest possible.

R.M: Is there a relationship between music and architecture, in your opinion?

G.P: Architecture is the main goddess of art. It contains music because we make noise in space when we move. It represents painting with its surfaces; it speaks in three dimensions like sculpture; it creates movement like cinema. Anyone who does architecture is a great creator. Be careful, however, not to confuse architecture, which is rare, with construction.

R.M: What about the connection between home and objects?

G.P: To understand a building type, you often have to see what furniture it contains: If you find a bed, mirrors, a kitchen and bathrooms, then it’s a living space; if there is an altar, candles, pews, or prayer mats, then it’s a temple; and if there are computers and other machines, then it’s an office. I believe that true architecture should be able to communicate its function without the need for objects.

“This moment is indeed liquid. That is why we must be free from ourselves, free from what was thought yesterday, and ready to understand the values of tomorrow. This instability is wonderful because it means every day is different.”